Constructing the Going-To-The-Sun Road, originally called the “Transmountain Highway”, was a major undertaking. It took nearly 3 decades to plan, design, and construct. Visitors today marvel at the route of the road and the ability to build it in such difficult terrain nearly a century ago.

Building access roads into this magnificent mountainous region began before it was designated Glacier National Park in 1910. Around the 1890s, Dimon Apgar and others homesteaded at the foot of Lake McDonald and Apgar built a two mile wagon trail from the Great Northern Railway station in Belton – now West Glacier – to the foot of the Lake McDonald.

George Snyder built a rustic lodge about 10 miles up on the east shore of Lake McDonald. The only access to his rustic lodge was by boat from the foot of Lake McDonald. John Lewis acquired the rustic lodge in 1909 and replaced it with a much grander hotel still in use today, as the Lake McDonald Lodge.

In 1910 when William Logan was named the park superintendent, he committed to substantially upgrading the wagon trail from Belton to the foot of Lake McDonald by 1911. Plans were made to build a road along the shores of Lake McDonald up to Lewis’s Lodge but Park Service funding was very limited and funding would be left to entrepreneurs. Since one could access the lodge by boat from the foot of Lake McDonald, the government was in no hurry to build the road so John Lewis embarked on the road construction project to his Lodge, and it was completed in 1922.

On the East Side of Glacier Park, Louis Hill, son of the Great Northern Railway founder, and the Great Northern Railway company itself, took on a building program during the park’s first decade. Glacier Park Lodge was built across from the railroad station in Midvale, now known as East Glacier. But construction didn’t stop there, they also built a 50-mile road along the East Side of Glacier Park starting at Midvale with spur roads extending a few miles into the Park, and at the end of each spur road, a rustic lodge was built. They also built chalets at Two Medicine, Cut Bank Creek, and St Mary Lake. And at the farthest north spur road, they built Many Glacier Hotel which is still in use today and for many years, was the largest hotel in Montana.

In the meantime, a variety of ideas were being proposed for the “Transmountain Highway” over the Continental Divide in the Lewis Range of the Rocky Mountains that would connect the East Side with the West Side of Glacier Park. One proposal by T. Warren Allen, who had planned roads in other National Parks, was to cross at the Kootenai Pass in the northern part of the Park. Another proposal by Prof. Lyman Sperry, an early explorer of the Park, was to cross at Gunsight Pass. One proposal even suggested the road go along the western shore of Lake McDonald and then wind its way up to Waterton Lake. Spur roads were proposed with this suggestion both to the left and right which would give people access to nearly every part of Glacier National Park.

In 1918, George Goodwin, acting superintendent of Glacier Park, convinced National Park Service director, Stephen Mather, that Logan Pass was the best place to build the “Transmountain Highway”. His proposal traveled along McDonald Creek to the confluence with Logan Creek and then climbed steeply along the Logan Creek Valley with 15 switchbacks, an 8% grade, and 50-foot radius turns, up the West Side to the Continental Divide at Logan Pass.

Congress appropriated $100,000 per year in the early 1920’s for the construction of the “Transmountain Highway”. Consequently, contracts were signed to begin construction from both sides. Eventually, they increased that appropriation to $1,000,000 each year for 3 years commencing in 1924.

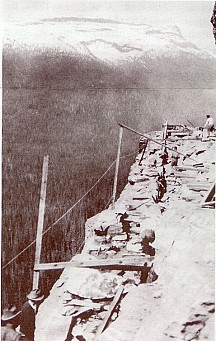

In 1924, Frank Kittredge, highway engineer for the Bureau of Public Roads, was brought in to survey the Goodwin route. The survey was started in September and Kittredge and his crew were pushing to complete the survey before winter. It was difficult work, sometimes climbing 3,000 feet each morning to start the day or hanging over cliffs and walking on narrow ledges. The work was so difficult, the turnover rate for his crew was 300 percent in the 3 months they worked on it.

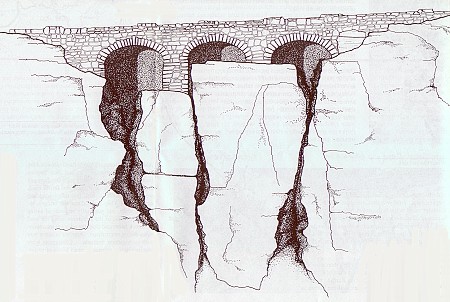

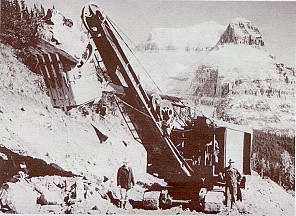

National Park Service landscape architects worked with the Bureau of Public Roads to develop the specifications for building the road. These specification insisted any bridges, retaining walls, and guardrails blend into the surrounding area which meant in most cases, rock from adjacent mountainsides were used to build these structures. They were also concerned about the construction method, it was determined large explosive blasts would cause too much destruction so contractors were required to use small explosive blasts. They even wanted to ban the use of power shovels but determined the exclusive use of hand labor would be too costly and the idea was squashed.

Thomas Vint, the National Park Service landscape architect, accompanied Mather and then Glacier Park Superintendent Charles Kraebel in 1924 when they inspected the construction progress. Vint opposed Goodwin’s route, he thought this route would leave a big scar on the scenic Logan Creek Valley. He protested and proposed a different route, a longer, straighter route with a 6% grade that had only one switchback with a 75-foot radius turn. Both routes followed McDonald Creek up to the confluence with Logan Creek. Vint’s route continued along McDonald Creek Valley ascending gradually until it switch-backed – the point now referred to as The Loop – and followed along the vertical cliffs of the Garden Wall to Logan Pass.

To resolve this conflict, Mather brought in Frank Kittredge, who eventually became the National Park Service highway engineer in 1927, to survey the routes. Kittredge liked the aesthetics of Vint’s route and recommended it, and Mather concurred. Aesthetics was an important consideration when designing and constructing the road. The road was built according to Vint’s proposal with the exception of a few modifications.

By the time they selected someone to build the West Side section of the “Transmountain Road” in 1925, 10 miles of the road had already been built along the north side of St Mary Lake, and roughly 12 miles along the east side of Lake McDonald to the head of the lake. The firm selected to build the West Side section of the road was Williams & Douglas Construction Company of Tacoma, WA with a bid of $869,145.

Due to the large amount of snow the Lewis Range receives each winter, construction could only be done in the summer months. The section of the road along the Garden Wall was the most difficult section to build because of the steep cliffs. The Williams & Douglas firm got a slow, late start in 1925 but by the end of the 1926 summer, the road was almost half complete. The West Side section was roughly 2/3 done by the end of the 1927 summer. Because of the 1929 fire on the West Side, and the Great Depression, very little construction occurred on the West Side in 1929 and 1930, but by the summers of 1931 and 1932, it was complete.

Most of the structures on the west side were built by Williams & Douglas Construction Company. These structures included the West Side Tunnel, the Logan Creek Bridge, the Triple Arches, the Haystack Creek Culvert, and all the retaining walls. They used power shovels and a small gasoline powered engine with twelve cars called a “dinky” train to move materials wherever they were needed.

Colonial Building Company of Spokane, WA and A.R. Guthrie Company of Portland, OR were awarded the contracts to build the “Transmountain Highway” on the East Side of Logan Pass. This 10-mile section of the road was also built in 1931 and 1932. The 405-foot tunnel was the most difficult project the Colonial Building Company constructed. Rock had to be carried out by hand because power equipment could not reach that section of the road. A.R. Guthrie had to float a power shovel up St Mary Lake to get it to his construction site.

After nearly 3 decades of planning and construction and over $2,000,000, the first automobile crossed over the “Transmountain Highway” in late fall of 1932. The “Transmountain Highway” was formerly opened in a special dedication ceremony on July 15, 1933. The ceremony was presided over by then Glacier Park

superintendent Elvind Scoyen and was attended by more than 4,000 people. A speech by the Montana State Highway Commission honored the late Stephen Mather for his vision to build a road through Glacier Park. Music was provided by the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Blackfeet Tribal Band. A ceremony of peace among the Blackfeet, Flathead, and Kootenai Tribes concluded the afternoon.

Amid extremely steep, difficult terrain and hazards from dynamite to grizzly bears, amazingly only 3 men lost their lives during the construction of the “Transmountain Highway.” One died from a fall and the other 2 were killed by falling rock.

In 1938, paving the “Transmountain Highway” began but wasn’t completed until 1952 as a series of paving contracts were interrupted by World War II.

The “Transmountain Highway” was officially named Going-To-The-Sun Road during the dedication ceremony in 1933. This name came from nearby Going-To-The-Sun Mountain. Legend has it, Going-To-The-Sun Mountain was named for a Blackfeet phrase about a spirit “who went back to the sun after his work was done.” Glacier Park superintendent, J.R. Eakin said this name “gives the impression that in driving this road autoists will ascend to extreme heights and view sublime panoramas.”

The Going To The Sun Road is roughly a forty minute drive from Smoky Bear Ranch.

Information extracted from Going-To-The-Sun Road by Bill Yenne and Mountain Mouse Land’s article Glacier National Park Going To The Sun Road Construction.